Sharing Circles, Food Sovereignty and Organising Bioregionally

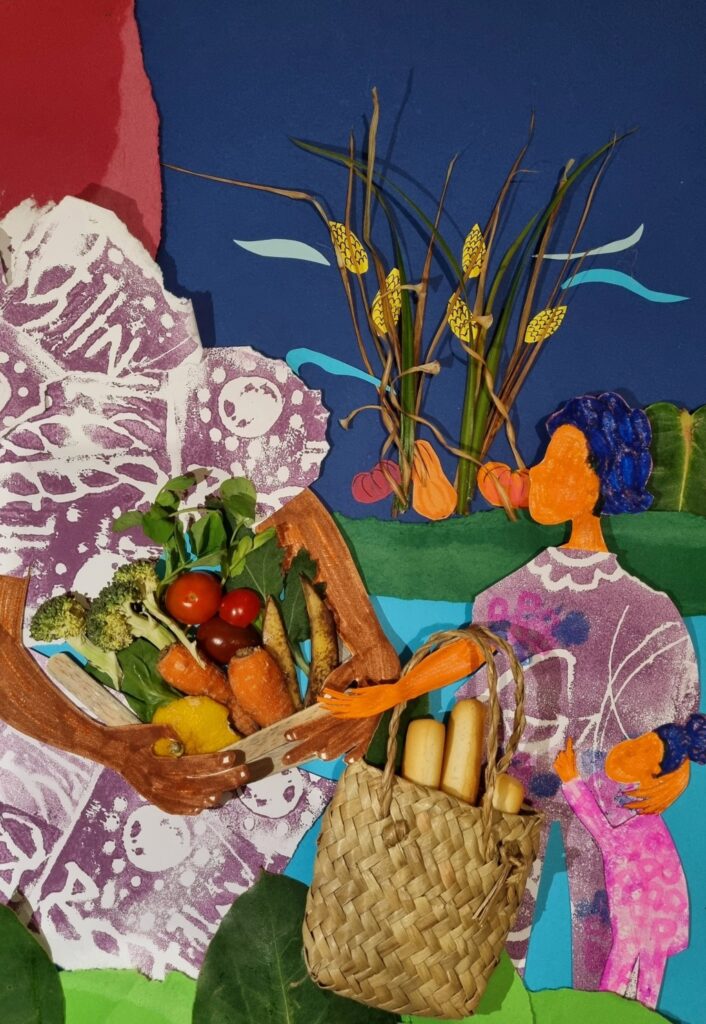

Globalised industrial food systems are unsustainable – huge carbon emissions, soil degradation, unsafe and unethical intensive livestock farming, and brittle supply chains and distribution leading to empty shelves being just some of the problems. So what can future-proof food systems look like, and what lessons can Scotland learn from traditional ecological knowledge from elsewhere? Catriona Spaven-Donn and Diana Garduño Jiménez weave together threads of food sovereignty activism in Scotland, bioregionalism and the Mayan sharing practice of the cuchubal. Illustration by Tarneem Al Mousawi.

Degrowth is a radical reimagining of the kind of society we need to create in order to protect our future. When extractivist economic and political systems have changed the very geology of our Earth and led us into the Anthropocene’s age of extinction, we clearly do need a different story.

In bringing together the threads of that story, we must weave cross-cultural thinking and traditional ecological knowledge into the future vision… for what is future is also what has passed.

As we reclaim, reimagine, and re-envision, we also question. Doubt creeps in about things we were told as fact – such as Darwinian theories of competition and the widely accepted idea that we need to compete to stay alive and thrive; that our world rewards the survival of the fittest. Suzanne Simard, renowned ecologist and author of Finding the Mother Tree: Uncovering the Wisdom and Intelligence of the Forest, describes her first encounter with mycorrhizal fungus roots and their two-way exchange of soil nutrients and photosynthesised sugars. (1) She realises that the mutualism of this relationship calls into question the idea that competition is essential to evolution and, rather, suggests that co-operation is key. She later writes about the symbiotic nature and diversity of the forest floor:

“I have come full circle to stumble onto some of the Indigenous ideals: Diversity matters. And everything in the universe is connected – between the forests and the prairies, the land and the water, the sky and the soil, the spirits and the living, the people and all other creatures.” (p.283)

Robin Wall Kimmerer, scientist and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, illustrates the same principle of reciprocity in Braiding Sweetgrass (2) through the indigenous agricultural system of the milpa or Three Sisters, the complementary planting together of starch-rich corn, nitrogen-fixing bean, and high-vitamin squash:

“The Three Sisters offer us a new metaphor for an emerging relationship between indigenous knowledge and Western science, both of which are rooted in the earth. I think of the corn as traditional ecological knowledge, the physical and spiritual framework that can guide the curious bean of science, which twines like a double helix. The squash creates the ethical habitat for coexistence and mutual flourishing. I envision a time when the intellectual monoculture of science will be replaced with a polyculture of complementary knowledges. And so all may be fed.” (p.139)

When 80% of global arable land is industrial monoculture and 75% of world food crop biodiversity has been lost (3), all being fed is no small thing. If we are to protect the diversity of our food systems and cultural identities, a shift in our structures of organisation is also imperative. Rather than a focus on colonial national borders, why do we not re-engage with the natural boundaries of rivers and mountains and consider what is possible within our own watersheds? In the context of a just transition to a world of radical sufficiency, this means organising bioregionally – relocalising our economies, shortening our supply chains, and living in harmony with the land around us.

Bioregionalism is a different and yet familiar story, an ancestral story of collective wellbeing and ecological approaches. Organising bioregionally is part of the process of achieving self-sufficiency through the co-operation, mutualism, and symbiosis that Simard and Wall Kimmerer suggest.

In Scotland, mycorrhizal networks of food growers and community gardens are flourishing, creating mutually beneficial relationships for people and planet. We have seen that in the context of Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic, people are paying more attention to food sovereignty, access to local produce, and farmers’ livelihoods. Is this the beginning of a paradigm shift towards sustainable and regenerative relationships with food and its production?

Abi Mordin, co-founder of Glasgow’s Community Food Network, calls for co-ordinated collective action in the face of COVID-19, Brexit, and climate change and their impacts on our food system. Along with a burgeoning network of grassroots food growers, she is working towards the diversification of our food production to create community resilience, food security, and affordable and healthy food for those who need it most.

The Scottish Communities Climate Action Network is also working to implement local solutions and a vibrant system of small-scale local democracy, while encouraging an abundance of local food growers and producers everywhere, including city centres, abandoned land, and temporary spaces. This vision includes the transmission and celebration of cross-generational knowledge exchange.

Similarly, Nourish Scotland works for a fair, healthy, and sustainable food system that truly values nature and people. Their Fork to Farm Dialogues are locally-led conversations focused on building trust and relationships between primary food producers and local decision-makers. The dialogues aim to bring farmers’ voices to the fore in the discussions around food systems, agriculture, just transition, and climate change. The Global Fork to Farm Dialogue will take place at COP26, bringing together 100 local government representatives with 100 practising farmers. The dialogues have so far engaged people from Mexico, Scotland, Belgium, Ecuador, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Tanzania. Ancestrality and plurality have been recurring themes of the dialogues. While Mexican participants have re-learned the milpa food system that Wall Kimmerer discusses, Scottish participants have also reconnected with the past in order to look to the future.

For one of the Scottish Fork to Farm participants, the Highland Good Food Partnership, the creation of a sustainable, local food system also involves the possibility of reviving the ‘shieling system’. In his article, ‘Ancient Futures for Highland Hills: Reinventing the Shielings,’ Col Gordon explains the shielings as a system in which cattle were herded from low-lying glens and woodlands to graze up in the mountain pastures during the summer months. This seasonal change also marked cultural festivals, local storytelling and song traditions. Gordon comments that “despite such a harsh environment, historically the native Highlanders carved out indigenous systems of subsistence that were perfectly balanced to their surroundings. Broadly speaking, these were very elegant, efficient and productive and operated within the means of the local ecologies.” (4)

With the introduction of sheep during the Clearances, the land quality deteriorated and native woodland was reduced at a much more rapid rate. Upland fertility encouraged by the shielings was degraded by the year-round presence of sheep and deer. Gordon suggests that a reintroduction of the shielings system, or an ancient future for Highland hills, could allow for local cheese and meat production as well as rewilding and agroforestry.

In Scotland, while we undeniably have a meaningful relationship with land and sea, colonial patterns of land ownership and the current pro-growth agenda of oil extraction, rapid urbanisation, and increasing consumption entail the use and abuse of nature, rather than an approach that integrates the health of humanity with the health of the planet.

What, then, is our recourse to living holistically and sustainably with and for nature?

The concept of the Commons exists across cultures. Enough! Scotland defines the Commons as “that which we all share that should be nurtured in the present and passed on, undiminished, to future generations. We might think of reclaiming the Commons as reclaiming our past and our future.” In the Maya K’iche language, the cuchubal means “we all contribute.” In Mayan communities throughout Central America, the tradition of the cuchubal entails monthly contributions to a common pool. Historically, this meant each family provided a different foodstuff – corn, black bean, squash – so all were provided for. Women led the process. Now, it usually involves the exchange of money as part of a microfinance sharing circle. Sharing circles, then, function like mycorrhizal networks; interconnected and interdependent groups of mutual exchange that act locally in order to ensure the health of the whole. The co-operation and collectivism of the cuchubal reflects the Commons and its reclamation of our past and future.

In Arturo Escobar’s book, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy and the Making of Worlds, (5) he suggests that ancestrality is the basis for autonomy. Ancestrality is an energising connection that people have to land through the knowledge that it was inhabited and cared for by their ancestors. Crucially, “far from being an intransigent attachment to the past, ancestrality stems from a living memory directly connected to the ability to envision a different future” (p.71).

Ancestrality acknowledges that other worlds exist and are possible. Wall Kimmerer mentions a “polyculture of complementary knowledges”, while Escobar defines the “pluriverse” as a plurality of stories that weave together both interdependence and autonomy. This diversity of cultures, identities, languages, food systems, and cosmovisions reflects the Zapatista decolonial, anti-capitalist, agroecologist, and equitable social theory of un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos – “a world where many worlds fit.” Zapatistas say that this ideology serves as a bridge to cross to the other side, to build a better world – a new world. Radical transformation involves a horizontalised system of mutual aid and reciprocal relations. It involves constructing, not destroying; to serve others, not oneself; to work from below, not supplant from above.

A new world does not entail invention of a new set of stories. It necessitates the revisiting of ancestrality and autonomy in order to achieve a world of many worlds, a world of complementary knowledges and mycorrhizal networks. Decoloniality moves us away from the notion that there is one single story and reinstates a celebration of diverse ways of living in and interacting with the world around us. While colonial forces imposed one single form of living, decolonial ideas encourage a plurality of co-existences; a community grounded in the celebration of difference.

Robin Wall Kimmerer writes that while humans can’t photosynthesise and create gifts through air, light, and water – we do possess language as “an act of reciprocity with the living land. Words to remember old stories, words to tell new ones, stories that bring science and spirit back together to nurture our becoming people made of corn” (p.347). In the Mayan sacred text, the Popul Vuh, people are born from corn, which in turn is made out of all four elements of earth, air, fire, and water.

“In the indigenous view, humans are viewed as somewhat lesser beings in the democracy of species… Plants were here first and have had a long time to figure things out. They live both above and below ground and hold the earth in place. Plants know how to make food from light and water. Not only do they feed themselves, but they make enough to sustain the lives of all the rest of us. Plants are providers for the rest of the community and exemplify the virtue of generosity always offering food. What if Western scientists saw plants as their teachers rather than their subjects? What if they told stories with that lens?” (p.346)

The story we might tell is one of reciprocity between people and planet and between past and future. We can learn from plants and the ways they provide, collaborate, and exchange.

Holistic agroecological food systems require a decolonial approach that is circular, decentralised, collective, collaborative, autonomous, and include ancestral wisdoms. In this way, we can achieve a vision for the future that encourages mycorrhizal growing networks in which our communities relocalise, horizontalise, and thrive, in which the complex plurality inherent in our biodiverse ecosystems is defended, celebrated, and protected. And ultimately, in this way, we can transition to the Zapatista epistemological vision of “un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos” – a world where many worlds fit – worlds of thriving small-scale crops, reclaimed spaces, localised food systems, and co-operative communities.

To hear more about the work of Nourish Scotland’s Fork to Farm Dialogues and the Glasgow Community Food Network, check out UN House Scotland’s Climate and Gender podcast series ‘Connecting Women’s Voices on Climate Justice’, (6) and have a listen to the second episode, From Scotland to Ecuador: Building Local Relationships for Healthy and Resilient Food Systems. (7)

Notes

- Suzanne Simard (2021) Finding the Mother Tree: Uncovering the Wisdom and Intelligence of the Forest. Allen Lane

- Robin Wall Kimmerer (2020) Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Penguin Random House

- Leonardo Figueroa Helland (2018, October 16) From Anthropocene Troubles to Utz K’aslemal: Indigenous Ecologies as Bioculturally-Diverse Pathways Beyond A World Of Crisndigenous-ecologies-and-bioculturally-diverse-pathways-beyond-a-world-of-crises-qaes. The New School Tishman Environment and Design Center. Available at: https://www.tishmancenter.org/blog/leonardo-figueroa-on-from-anthropocene-troubles-to-utz-kaslemal-i

- Col Gordon (2020, September 10) Ancient Futures for Highland Hills: Reinventing the Shielings. Highland Good Food Partnership. Available at: https://highlandgoodfood.scot/ancient-futures/

- Arturo Escobar (2017) Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press.

- United Nations House Scotland, Connecting Women’s Voices on Climate Justice: Perspectives from Scotland and Around the World [podcast series]. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/show/0vKLpICd7YUE12LA8tMMa8 Also see: https://www.unhscotland.org.uk/podcasts

- Catriona Spaven-Donn, Carolina Salazar Daza, Sofie Quist, Abi Mordin (2021, July 27) ‘From Scotland to Ecuador: Building Local Relationships for Healthy and Resilient Food Systems’ [podcast], Connecting Women’s Voices on Climate Justice: Perspectives from Scotland and Around the World, United Nations House Scotland. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/episode/4SPl1TdBQpWbbJwF57FNcZ