In this article, I argue against the growth-based model of the cultural industries, focusing on cinema and thinking towards alternative pathways for a post-growth creative sector in Scotland. In the months since I started writing it, many of the things I argued about have ground to a halt due the Covid-19 pandemic. Production projects have stalled, venues have closed, awards have been postponed and festivals moved online. As people’s livelihoods hang in the balance, it needs to be said that this crisis is not a solution to the problems with the status quo. Indeed, its tendency is to reinforce the concentration of power, as the sector reacts defensively and closes down spaces for experimentation. Returning to this analysis while the situation remains very uncertain is a risky exercise, but I do it in the hope that, amongst the grief and the fear, there is also a critical desire for a different life in and out of this impasse.

Amongst the hardships that people have endured throughout the pandemic times, the closure of cinemas is amongst the least significant. That is, of course, unless you work in the film exhibition sector, in which case you are likely to be one of the millions of precarious workers who have found themselves unable to access furlough schemes or other forms of support. As screening venues closed their doors in March, film and TV production schedules also stopped, leaving their freelance crews unsure of when they may work again. Meanwhile, as sociability was curtailed in the interest of preventing contagion, the role of media in connecting people and offering some lightness has been keenly appreciated. Some audiences have enjoyed unprecedented access to films online and on broadcast, with filmmakers sharing their work for free, festivals emerging from all over the world, and even new work exploring experiences of lockdown using constraints as creative prompts. Streaming platforms saw an opportunity and seized it, with Netflix gaining twice as many subscribers as expected, and Disney+ moving in to capitalise on the childcare gap. Considering that 87% of Scottish households have internet access, but only about 13% of adults go to the cinema more than once a month, it would seem that this move online can be a democratising one. However, if this remains only an exercise in market expansion and capture by streaming platforms, there is little cause for celebrating the temporary collapse of the cinema business.

There is an imbalance between the social value ascribed to the arts in general and film in particular, and the precariousness of its survival in a recession. My attempt to see a different future through this fog seeks to imagine a just transition where such insecurity is not the norm for workers, without trying to salvage the many unsustainable aspects of their jobs. In order to think beyond this crisis and towards a post-growth film culture in Scotland, we need to centre the needs of people, communities, and the environment, rather than the profit of media corporations and their local retail outlets.

As an industrial product, cinema has long been subject to the expansionist logic of investment markets, financial or otherwise. Since the birth of Hollywood, the mainstream film production system has been an oligopoly, and it is now fully enmeshed in webs of corporate takeovers that span all branches of the media. Outside the US, the influence of this model has shaped local attempts to create an ‘industry’, whereby public money is used to subsidise infrastructure and appeal to investors. On the margins of these industrial dreams, cultural workers scrape a living from thoroughly insufficient public support, predicated on a model of the ‘creative and cultural industries’ tied to economic growth and competition. The current brake on this treadmill can help reveal the inequity of this approach.

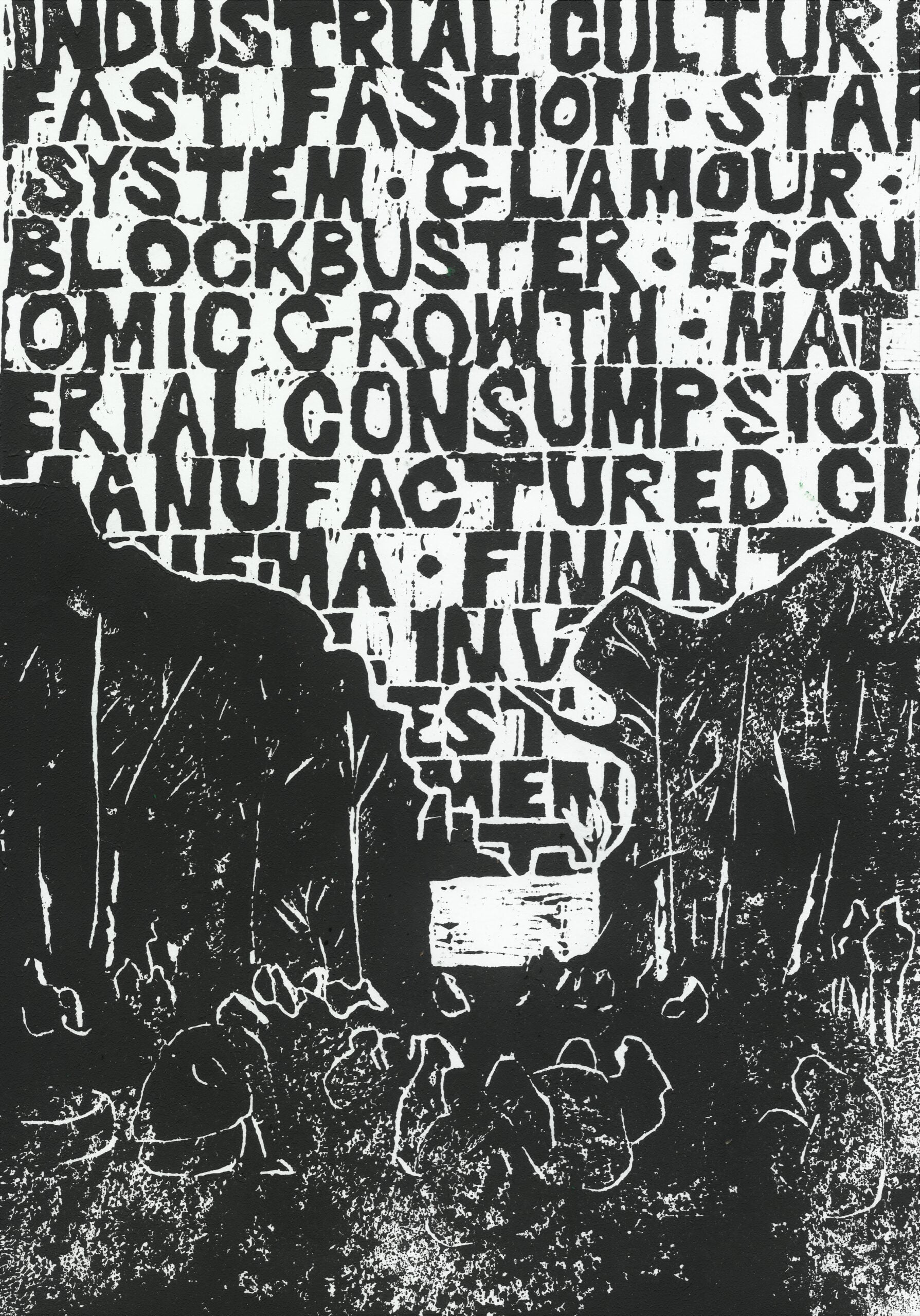

As well as being economically unjust and culturally undernourishing, our dominant media models are wasteful, polluting, and underpinned by colonialist and extractivist processes. In her book The Cinematic Footprint, Nadia Bozak argues that “cinema is intricately woven into industrial culture and the energy economy that sustains it”. From the very beginning, the manufacture of raw film stock polluted groundwater, ate up large amounts of silver and camphor, and required millions of gallons of water every day. It would seem like today’s digital cinema does away with those issues, until we consider the rare-earth minerals in screens and circuits, the batteries, and the server farms that run VFX graphics processing and streaming platforms. The problems have changed, but the extractivist and competitive underpinnings remain.

A film culture informed by climate justice and deep adaptation needs to take these impacts seriously. In what follows I make an argument for a reduce-reuse-recycle approach to the film industry, and a hopeful outline of what a post-growth film culture may look like.

Reduce: Against the blockbuster

The first problem of thinking about cinema in a post-growth Scotland is that it is not by any means obvious that it should exist. Purely on environmental grounds, even a mid-budget film causes Co2 emissions comparable to the annual footprint of thousands of UK inhabitants, and sends tons of timber to landfill, so it is worth considering whether all of this is justifiable.

As with most spaces where a degrowth strategy is needed, distinctions soon emerge between a concentrated, resource-intensive layer at the top, and a much more organic ecosystem below. In the media world, there are the blockbusters and glossy serials produced by a small number of media corporations. These titles have an oversize impact in terms of budget, resource use, box office and cultural visibility. According to UNESCO statistics, in 2016 just over nine thousand feature films were released. Three-quarters of these came from six countries: India, China, United States, Japan, Korea and the UK. However, the US alone captures over 70% of the global box office, while a single company (Disney) distributed seven out of the ten top movies. A typical film from Marvel Studios, now owned by Disney, has a budget of 200 to 400 million dollars, which is at least ten times as much as the average UK or Korean film. This is then a global industry where the profits flow towards a handful of corporations.

This mode of production demands programmed obsolescence, as each new film has to be sold to larger audiences, or more affluent ones. As Maxwell and Miller argue, “[t]here is a structural homology between this disposable attitude to film production and forms of consumption oriented to fast fashion, fun, and a throwaway culture”, where each fad must quickly make way for the next indistinguishable ‘unprecedented’ product. This high-stakes game is incompatible with the wellbeing of film workers and the reduction of environmental impact. While new voices and ideas may be incorporated every so often, overall the system manages risk by repeating itself, and hence reproducing its systemic racism, sexism, transphobia, and class-based gatekeeping.

There are strong movements for reform within this production model, from #MeToo and #OscarsSoWhite activism to the inclusion of ‘diversity riders’ in studio contracts. Since the 1990s, several ‘green’ initiatives have emerged within media industries, seeking to stave off external regulation and win over public opinion through voluntary schemes, such as sustainability consultancy, carbon offsetting, improved recycling, rechargeable batteries, and reuse of props and sets. However, these schemes often have an overly narrow definition of environmental impact, and their attachment to profit as a main driver means that they end up being ‘greenwashing’ or branding exercises, even when the efforts of the workers on set are genuine.

Most blockbuster-style films simply cannot be made sustainably, no matter how much they spend on carbon credits. See, for example, Kevin B Lee’s video essay on the making of Transformers 4, with its multiple transcontinental locations, its explosions and helicopter shots. Perhaps it would be unfair to expect a film about big trucks to go for net zero, but it is easy to see how the financial logic of transnational coproduction encourages wasteful shooting practices.

Many countries, Scotland included, have hitched their cultural policy wagon to this continent-hopping location shooting, offering scenic landscapes, skilled workforces and tax exemptions to lure producers. And yet, regardless of how many lochs, glens and castles you can put on a location guide, they will be subsumed into what Jennifer Kay calls a “simulationist aesthetic”, with “fake trees made out of wood and artificial rain made with water”. In that system, films shot in Scotland may have very little to show or say about it; their relationship to the landscape and the people is an extractive one.

PEOPLE USE FILMS TO THINK AND FEEL WITH, AND SHARING IMAGES, SOUNDS AND STORIES GIVES THEM WAYS TO RELATE TO ONE ANOTHER, TO THEMSELVES AND TO THE WORLD. THESE ARE THE THINGS WE NEED FOR A GOOD LIFE. BUT THE USE OF RESOURCES NEEDS TO BE MORE PROPORTIONATE AND, ABOVE ALL, FAIRER.

People use films to think and feel with, and sharing images, sounds and stories gives them ways to relate to one another, to themselves and to the world. These are things that we need for a good life. But the use of resources needs to be more proportionate and, above all, fairer. Greater diversity in casting and storylines has been applauded as the sign of change, but a just transition approach to film production would mean abandoning big studio cinema (whether mainstream or arthouse) in order to make space for the minor. This is the abundance of creativity, thought, observation and expression already thriving through collaboration rather than competition. I am thinking of indigenous cinema; films by trans and non-binary people, by neurodiverse and disabled people, by black people, and people of colour; radical political cinema, experimental films, long slow films, extremely short films; films of local interest or profoundly niche appeal; and all the intersections between categories, all the boundary-crossings that become possible across the margins when the centre is struck down.

A just transition would reject the premises of blockbuster cinema. It would advocate for slower, more collaborative, and resourceful creativity, giving films and filmmakers the time to find their voice and reach audiences at their own pace. This requires us to rethink the temporality of film circulation. The media corporations’ hold on screens and profits is maintained through a stranglehold on the legal distribution of new titles, which makes it comparatively difficult for independent, low-budget films from around the world to reach audiences. The suspension of filming due to Covid-19, and the closure of cinemas worldwide, has wreaked havoc with the film release schedule, which is organised around the summer blockbusters. This interruption of the franchise treadmill offers a moment of respite and a glimpse of what could be supported instead.

Reuse: Against the coming attractions

Mainstream films have always been sold as perishable items: they peak on the opening weekend and quickly fade from public awareness, replaced by the next star-fronted blockbuster. More specialised films may have a slower circulation through film festivals and arthouse screens, but such spaces also privilege new releases. Only a handful of films make it into the prestige lists to become occasionally resurrected as classics. Film circulation before Covid-19 had an absurdly wasteful cycle, like the best-before dates on long-life supermarket food.

Unlike food, however, film doesn’t actually go off, and hence a lack of releases does not create scarcity. At home, audiences have been finding their way to older films. Repertory channels like Talking Pictures TV have seen their audience numbers soar, film archives have been presenting online programmes, and the Black Lives Matter movement has brought forward an overdue appreciation of Black film history. The lockdown experience shows that if older films are seen, celebrated, contextualised and accessible, a richer film culture is possible with fewer new films. Each encounter between film and audience produces, in its localised way, a new film experience. Switching off the blockbuster hype machine gives audiences more chances to find the films that speak to them.

This is not only a matter of availability. Back when Netflix was still a DVD mail-delivery company, Wired columnist Chris Anderson used it as an example of his influential model of the ‘long tail’ of online media distribution, which showed how the on-demand model would make old films commercially valuable. However, 15 years later, this model has done little to challenge the dominance of a decreasing number of film productions. Instead, the streaming companies compete with one another by hyping up a constant flow of new content, while the back catalogues dwindle and fade from view. The dispersed library of global cinema available online may offer opportunities for film buffs with the disposable time and money to seek it out, but popular media consumption has continued to concentrate on a handful of crowd-pleasing products.

Algorithmic recommendation systems are designed as traps, optimised to swallow up leisure time so that the subscription becomes indispensable. They are more likely to serve up more of the same, with just enough variation. Recommendations are crucial to save consumers from feeling overwhelmed by choice, particularly in an anxious era where people are made to feel personally responsible for judging the ethical and environmental impacts of each decision. But we may need to look beyond algorithms in order to rebalance collective and individual choice, to counteract both fragmentation (filter bubbles) and concentration (blockbuster culture). Nothing new needs to be invented for this to happen: film clubs have existed for a hundred years, allowing people to get together and make collective choices, and to sustain a shared viewing experience that doesn’t depend on obsolescence cycles.

To combat the predictability and shallowness of algorithmic recommendations, we can look to the people who have been doing the work of choosing and programming films outside conventional new releases. Repertory programmers, cine-club and film society committees, archive researchers, librarians, and community organisers have been sharing their discoveries, presenting films that may not be new but are relevant to a particular situation or place, that resonate with an audience, or that are simply too good to forget. Their online activities during Covid-19 have allowed them to reach new audiences. However, the guidelines for safe public gatherings will affect their ability to resume screenings differently; while some may be better prepared than commercial cinemas, others may struggle in smaller, shared venues. Initiatives like Radical Home Cinema, where people visit each other’s houses and share hospitality as well as films, may take a while to restart, but can be one of the many variants of what cinema can be beyond the multiplex.

Recycle: Against single-use films

Watching more old films would already reduce the need for new films, but expressions of the present are still important. Old films again may offer a way to reduce the impact of creating new work. There is an ocean of footage lapping at our feet, and from its depths, new works can emerge, with no need for new shooting expeditions or energy-guzzling studios. Filmmakers are increasingly awake to the potential of archival and found footage as a creative element. Reused images can have a conventional historical function, or they can be expressive, critical, experimental, and intriguing. Found-footage films have been around for a long time, allowing artists to create meaning and excitement without the expense of shooting. In doing so, they have provided an implicit critique of ‘the disposable nature of contemporary consumer culture’.

Remix films are another way of defying the obsolescence model in film culture, and instead re-inscribe meaning-making and creativity as a circular process. One of the biggest obstacles to this circularity is the institution and enforcement of intellectual property. There is a different discussion to be had about the necessity of ensuring that people can have a livelihood without depending on meagre royalties, but current copyright regimes are not defensible on that basis. One needs only to look at how media corporations pursue takedown actions against individual YouTubers for their critical use of clips, to realise that the disproportionate enforcement of intellectual property continues to benefit corporate interests above actual artists and creatives.

As Kropotkin wrote,

‘[t]here is not even a thought, or an invention, which is not common property, born of the past and the present […] By what right then can any one whatever appropriate the least morsel of this immense whole and say—This is mine, not yours?’

Each piece of media embeds substantial amounts of common energy and resources. If the vast repositories of existing moving images become a common source from which to make new combinations, then it is possible to recirculate that energy instead of creating more waste. As a “metahistorical work”, the remix can contribute to urgent new understandings of history, unravelling the linear framework of progress. More tactically, recycled media can be used in what the situationists called detournement, or media jujitsu, where the strength of media persuasion and spectacle can be turned against its capitalist foundations. According to filmmaker Craig Baldwin, remixing and found-footage film-making traditions have a lot in common with folk art, and in these informal practices there is potential for a more democratic access to the means of production. The popularisation of remixing as a folk practice doesn’t have to sacrifice its “adventurous and insurgent character”.

There are plenty of examples online, more recently on social media platforms like TikTok, to show that remixing and recycling media objects has the potential to be at the same time popular, accessible, and critical. This is not a niche or avant-garde corner of the art world, but an everyday vernacular. Reclaiming archive images can produce radical encounters with history, contesting racism as in Handsworth Songs (Black Audio Film Collective, 1986) or extractivism as in Fly me to the Moon (Esther Figueroa, 2019). Scotland has its own crop of thought-provoking uses of archive, from the playful medley of From Scotland with Love (Virginia Heath, 2014), to the weaving of old and new analogue footage in All Divided Selves (Luke Fowler, 2011), or the surfacing of women’s perspectives in Her Century (Emily Munro, 2019). With a rich legacy of moving images to draw on, and new questions to ask of them, this can be a form of minimal-impact filmmaking that reclaims the throwaway and contests the disposability of the medium.

Watching together

While archive film is thriving online, it is important to keep utopian fantasies about the internet in check. Even The Economist recognises that, “as a business, entertainment has in some ways become less democratic, not more. Technology is making the rich richer, skewing people’s consumption of entertainment towards the biggest hits and the most powerful platforms”. Therefore, transforming creative practices needs to be accompanied by changes in media consumption.

The solutions offered so far to the Covid-19 crisis in the screen industries have a pull towards the private. Streaming serves individual consumers and promotes an illusion of personal choice. It offers a technological remedy for social problems, such as the exclusion of disabled audiences and the geographical disparities in access to film. At the same time, new initiatives such as drive-in cinemas and exclusive screenings have emerged to cater to the better-served, affluent audiences. There is then a risk that the ‘new normal’ for the cinema industry will be a hollowing out of its public function, and a continuation of energy-intensive, wasteful practices. It is true that domestic screens have become increasingly efficient, but the amount of information flowing through circuits, cables, satellites, and data centres to serve on-demand media consumption is still ballooning. Although providers of web services have moved faster than other industries towards sustainable energy sources, the speed of growth threatens to outrun these efforts, with Amazon for instance turning back to fossil fuels to power some of its data centres. So, even on this metric alone, the benefits of streaming need to be assessed critically. And I hardly need to expand on the case against drive-ins.

RESISTANCE IS BOTH PRAGMATIC AND UTOPIAN. IT IS ABOUT SUSTAINING A SPACE WHERE THINGS CAN HAPPEN AND PEOPLE CAN MEET. IN THE SIMPLICITY OF THIS ASPIRATION THERE IS MUCH TO LEARN FOR THE FUTURE DIRECTIONS OF CULTURAL ACTIVITY.

Getting together to watch films is a traditional practice that defies the imperative of convenience and personalisation. But if watching films together is to have a future in a low-carbon world, the purpose-built cinema is not the best venue for it. Instead, once it is safe to do so, we could have ephemeral cinemas in each neighbourhood: in people’s living rooms, in community halls, schools, parks, lecture theatres, pubs, cafes, and bike shops. There is no need for a cinema to be just a cinema; it may instead be one of the happenings that sustain a multipurpose venue. This premise is already in practice in the community cinema movement, in independent exhibition festivals such as Scalarama, and across several DIY spaces that have cinema at their heart, such as the Star and Shadow in Newcastle, the Cube in Bristol, or the Deptford Cinema in London. Christo Wallers of the Star and Shadow calls this a ‘relational’ mode of film exhibition, where “community is invoked as an act of cultural resistance to the transactional, individualistic structuring of dominant cinema”. This resistance is both pragmatic and utopian. It is about sustaining a space where things can happen and people can meet. In the simplicity of this aspiration there is much to learn for the future directions of cultural activity.

References

Anderson, Chris. 2004. ‘The Long Tail’. Wired, October 1. https://www.wired.com/2004/10/tail/.

Ashe, Melanie. 2019. ‘“With Great Power”: Spinning Environmental Worlds and “Green” Production in The Amazing Spider-Man 2’s Marketing’. Media Industries Journal 6 (1). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0006.101.

Bozak, Nadia. 2011. The Cinematic Footprint: Lights, Camera, Natural Resources. Rutgers University Press.

Debord, Guy and Gil Wolman. 1956. A User’s Guide to Detournement. First published in Les Lèvres Nues 8. Translation by Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology (Revised and Expanded Edition, 2006). http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/detourn.htm. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020.

Groo, Katherine. 2012. ‘Cut, Paste, Glitch, and Stutter: Remixing Film History’. Frames, no. 1 (October). http://framescinemajournal.com/cutpasteglitch.

Danks, Adrian. 2006. ‘The Global Art of Found Footage Cinema’. In Traditions in World Cinema, 241–53. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Fay, Jennifer. 2018. Inhospitable World: Cinema in the Time of the Anthropocene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kropotkin, Peter. 1906. The Conquest of Bread. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-the-conquest-of-bread

Maxwell, Richard, and Toby Miller. 2020. How Green Is Your Smartphone? Digital Futures. Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA: Polity.

Maxwell, Richard, and Toby Miller. 2012. Greening the Media. New York: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Brian. 2019. ‘Amazon Is Aggressively Pursuing Big Oil As It Stalls Out On Clean Energy’. Gizmodo Australia. April 9. https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2019/04/amazon-is-aggressively-pursuing-big-oil-as-it-stalls-out-on-clean-energy/.

Napoli, Philip M. 2016. ‘Requiem for the Long Tail: Towards a Political Economy of Content Aggregation and Fragmentation’. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 12 (3): 341–56. doi:10.1386/macp.12.3.341_1.

Oakley, Kate, and Jonathan Ward. 2018. ‘The Art of the Good Life: Culture and Sustainable Prosperity’. Cultural Trends 27 (1): 4–17. doi:10.1080/09548963.2018.1415408.

Petrusich, Amanda. 2020. ‘The Day the Music Became Carbon-Neutral’. The New Yorker, February 18. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-day-the-music-became-carbon-neutral.

Prelinger, Rick. 2013. ‘We Have Always Recycled’. Sight & Sound, 15 November 2013. http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/rick-prelinger-we-have-always-recycled/

Wallers, Christo. 2020 (forthcoming). ‘Cinema communities and community cinema – a relational practice?’. Filmo 2.